Why Did the Framers Create the Electoral College?—1st in a Series

Why Did the Framers Create the Electoral College?—1st in a Series

- November 26, 2017

Colorado

Coloradowent Democrat in the last presidential election. But three of those

elected as presidential electors wanted to vote for someone other than

Hillary Clinton. Two eventually cast ballots for Clinton under court

order, while one—not a party to the court proceedings—opted for Ohio

Governor John Kasich, a Republican. After this “Hamilton elector” voted,

state officials voided his ballot and removed him from office. The other electors chose someone more compliant to replace him.

Litigation over

the issue still continues, and is likely to reach the U.S. Supreme

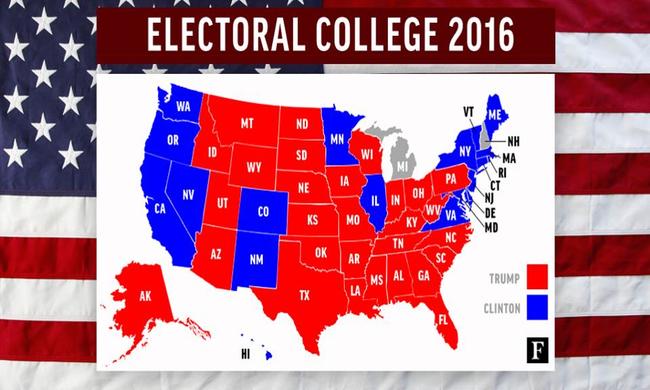

Court. Moreover, President Trump’s victory in the Electoral College,

despite losing the popular vote, remains controversial. So it seems like

a good time to explore what the Electoral College is, the reasons for

it, and the Constitution’s rules governing it. This is the first of a

series of posts on the subject.

The delegates to the 1787 constitutional convention found the

question of how to choose the federal executive one of the most

perplexing they faced. People who want to abolish the Electoral College

usually are unfamiliar with how perplexing the issue was—and still is.

Here are some of the factors the framers had to consider:

* Most people never meet any candidates for president. They have very

little knowledge of the candidates’ personal qualities. The framers

recognized this especially would be a problem for voters considering

candidates from other states. In a sense, this is less of a concern

today because, unlike in 1787, we have mass media through which

candidates can speak directly the voters. In other ways, however, it is more

of a concern than it was in 1787. Our greater population renders it

even less likely for any particular voter to be personally familiar with

any of the candidates. And, as I can testify from personal experience,

mass media presentations of a candidate may be 180 degrees opposite

from the truth. One example: media portrayal of President Ford as a

physically-clumsy oaf. In fact, Ford had been an all star athlete who remained physically active and graceful well into old age.

* Voters in large states might dominate the process by voting only for candidate from their own states.

* Generally speaking, the members of Congress would be in a much

better position to assess potential candidates than the average voter.

And early proposals at the convention provided that Congress would elect

the president. However, it is important for the executive to remain

independent of Congress—otherwise our system would evolve into something

like a parliamentary one rather than a government of three equal

branches. More on this below.

* Direct election would ensure presidential independence of

Congress—but then you have the knowledge problem itemized above. In

addition, there were (and are) all sorts of other difficulties

associated with direct election. They include (1) the potential of a few

urban states dictating the results, (2) greatly increased incentives to

electoral corruption (because bogus or “lost” votes can swing the

entire election, not just a single state), (3) the possibility of

extended recounts delaying inauguration for months, and (4) various

other problems, such as the tendency of such a system to punish states

that responsibly enforce voter qualifications (because of their reduced

voter totals) while benefiting states that drive unqualified people to

the polls.

* To ensure independence from Congress, advocates of congressional

election suggested choosing the president for only a single term of six

or seven years. Yet this is only a partial solution. Someone elected by

Congress may well feel beholden to Congress. And as some Founders

pointed out, a president ineligible for re-election still might cater to

Congress simply because he hopes to re-enter that assembly once he

leaves leaves office. Moreover, being eligible for re-election can be a

good thing because it can be an incentive to do a diligent job. Finally,

if a president turns out to be ineffective it’s best to get rid of him

sooner than six or seven years.

* Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts suggested election by the state

governors. Others suggested election by state legislatures. However,

these proposals could make the president beholden to state officials.

* The framers also considered election of the president by electors

elected by the people on a strict population basis. Unless the Electoral

College were very large, however, this would require electoral

districts that combined states and/or cut across state lines. In that

event, state law could not effectively regulate the process. Regulation

would fall to Congress, thereby empowering Congress to manipulate

presidential elections.

* In addition to the foregoing, the framers had to weigh whether a

candidate should need a majority of the votes to win or only a

plurality. If a majority, then you have to answer the question, “What

happens if no candidate wins a majority?”On the other hand, requiring

only a plurality might result in election of an overwhelmingly unpopular

candidate—one who could never unite the country. The prospect of

winning by plurality would encourage extreme candidates to run with

enthusiastic, but relatively narrow, bases of support. (Think of the

possibility of a candidate winning the presidency with 23% of the vote,

as has happened in the Philippines.)

The delegates wrestled with issues such as these over a period of

months. Finally, the convention handed the question to a committee of

eleven delegates—one delegate from each state then participating in the

convention. It was chaired by David Brearly, then

serving as Chief Justice of the New Jersey Supreme Court. The committee

consisted of some of the most brilliant men from a brilliant

convention. James Madison of Virginia was on the committee, as was John Dickinson of Delaware, Gouverneur Morris of Pennsylvania, and Roger Sherman of Connecticut, to name only four of the best known.

Justice Brearly’s “committee of eleven” (also called the “committee

on postponed matters”) worked out the basics: The president would be

chosen by electors appointed from each state by a method determined by

the state legislature. It would take a majority to win. If no one

received a majority, the Senate (later changed to the House) would

resolve the election.

No comments:

Post a Comment